Prior to the American Civil War, it was popularly assumed that states which had freely chosen to enter the Union could just as freely withdraw from said union at their own discretion. Indeed, from time to time individual states or groups of states had threatened to do just that, but until 1860 no state had actually followed through on the threat.

Since then, it has been considered axiomatic that the War “settled the question” of whether or not states had the right to secede. The central government, backed by force of arms, says the answer is No. As long as no state or group of states tests the central government’s resolve, we can consider the question to be “settled” from a practical viewpoint.

This assertion has long troubled me from a philosophical and moral viewpoint. We are supposedly a nation of laws, and the central government is supposedly subservient to the laws that established and empower it.

In a nation of laws, when someone asks, “Do states have a right to secede from the Union?”, a proper answer would have one of two forms:

- “Yes, because x.”

- “No, because x.”

Here, x would be an explanation of the laws that supported the Yes or No answer.

With the secession issue, though, we are given the following as a complete and sufficient answer:

“No, because if any state tries to secede, the central government will use force of arms to keep it from succeeding.”

There is no appeal to law in this answer – just brute force.

Based on this premise, the central government can amass to itself whatever right or power it chooses, simply by asserting it. After all, who has the power to say otherwise?

Come to think of it, that’s exactly how the central government has behaved more often than not since the Civil War.

This issue came to mind today because of an item posted today on a trial lawyer’s blog (found via Politico). The lawyer’s brother had written to each of the Supreme Court justices, asking for their input on a screenplay he was writing. In the screenplay, Maine decides to secede from the US and join Canada. The writer asked for comments regarding how such an issue would play out if it ever reached the Supreme Court.

Justice Antonin Scalia actually replied to the screenwriter’s query. I have a lot of respect for Scalia regarding constitutional issues, but his answer here is beyond absurd.

I am afraid I cannot be of much help with your problem, principally because I cannot imagine that such a question could ever reach the Supreme Court. To begin with, the answer is clear. If there was any constitutional issue resolved by the Civil War, it is that there is no right to secede. (Hence, in the Pledge of Allegiance, "one Nation, indivisible.")

He actually said that a constitutional issue was settled by military action. Oh, and by including the word “indivisible” in the Pledge of Allegiance, the issue became even more settled.

What if the president were to send out the troops to prevent the news media from publishing or broadcasting anything critical of his administration? This is clearly an unconstitutional action, but by Scalia’s logic, if the president succeeds, we must then say that the military action “settled the question” of free speech.

If these scenarios are not comparable, I’d like to hear why.

Here in Texas, whenever someone puts a serious dent in a guardrail, the highway department will send out someone to put up signs alerting us to this fact.

Here in Texas, whenever someone puts a serious dent in a guardrail, the highway department will send out someone to put up signs alerting us to this fact.

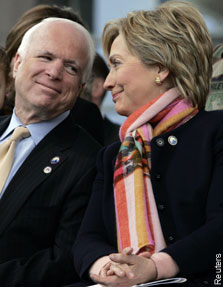

So. Bush administration officials assured you that the money would be used in a particular way. Then, you and your staff combed through the proposed legislation and found that yes, safeguards were in place to ensure that the money would indeed be used in the way specified by the officials. Thus, with confidence you cast your vote in favor of the TARP legislation.

So. Bush administration officials assured you that the money would be used in a particular way. Then, you and your staff combed through the proposed legislation and found that yes, safeguards were in place to ensure that the money would indeed be used in the way specified by the officials. Thus, with confidence you cast your vote in favor of the TARP legislation. with other men's freedom. He believes that this objective requires that power be dispersed. He is suspicious of assigning to government any functions that can be performed through the market, both because this substitutes coercion for voluntary cooperation in the area in question and because, by giving government an increased role, it threatens freedom in other areas."

with other men's freedom. He believes that this objective requires that power be dispersed. He is suspicious of assigning to government any functions that can be performed through the market, both because this substitutes coercion for voluntary cooperation in the area in question and because, by giving government an increased role, it threatens freedom in other areas."